Old Architecture: What is the Bridge?

To understand the Bridge, we need to understand how a React Native application works, because without understanding this, it's not possible to understand the Bridge.

What happens? We have an app developed with RN, inside the repository, we have several JS files (contexts, components, routes, etc). Just like on the web, these files are bundled into a single bundle. In React Native, it's similar, in the end we have a bundle, but unlike the web where we use WebPack for this, in React Native we use a tool called Metro.

Of course, unlike the web, where we have a JS bundle with everything (html, css, logic, etc), in mobile apps with RN this doesn't happen.

The reason is that RN applications render the interface natively (yes, in the end it becomes UIView, AndroidView and other native components). So, we don't just have JS, we'll have native implementations and consequently native code. So, we'll have JS code and native code (Objective-C, Java or Kotlin depending on the version, and Swift).

Therefore, we have a JavaScript VM (it's an engine responsible for interpreting our JS, similar to the V8 engine in Node.js). Before, it was JavaScript Core (same engine as Safari). But today, in the latest versions, a new engine was created: Hermes (specific for React Native, lighter, more performant).

Ok, now you understand important things:

- Metro: React Native bundler

- Hermes: JavaScript engine optimized for RN

- Native rendering: the UI is rendered with native components

Now, knowing that on one side we have Hermes (JS engine) and on the other side we have native code (Java/Kotlin and Objective-C/Swift), the question arises: what is each one responsible for?

The JavaScript layer is responsible for logic, that is, functions, hooks, rendering, everything we write stays inside JavaScript.

The native side: responsible for rendering and displaying the user interface. That is, assembling elements on the screen (UIView, AndroidView, etc), this is rendered and executed by the native side. Events, scrolls, etc.

Now, a question: how does the native side, which is made in a completely different language, communicate with JavaScript? How does Hermes communicate with the part responsible for generating the interface (native layer)?

This is only possible because of something called Bridge. That is, the Bridge makes the bridge between JS and Native.

In simple terms, the Bridge makes communication between the native side and JavaScript (and vice versa).

Now, another question: what is this Bridge like? What language is it developed in? It's low level, right?

The truth is that it's as simple as it sounds. The Bridge performs communication asynchronously, queuing messages between threads, and data is serialized in JSON to standardize the exchange.

For example: I pressed a button (native layer) -> the touch event is sent to JS. How is it sent? Through the Bridge. And in what format does it arrive to JavaScript? In JSON. Simple. And vice versa (the reverse path).

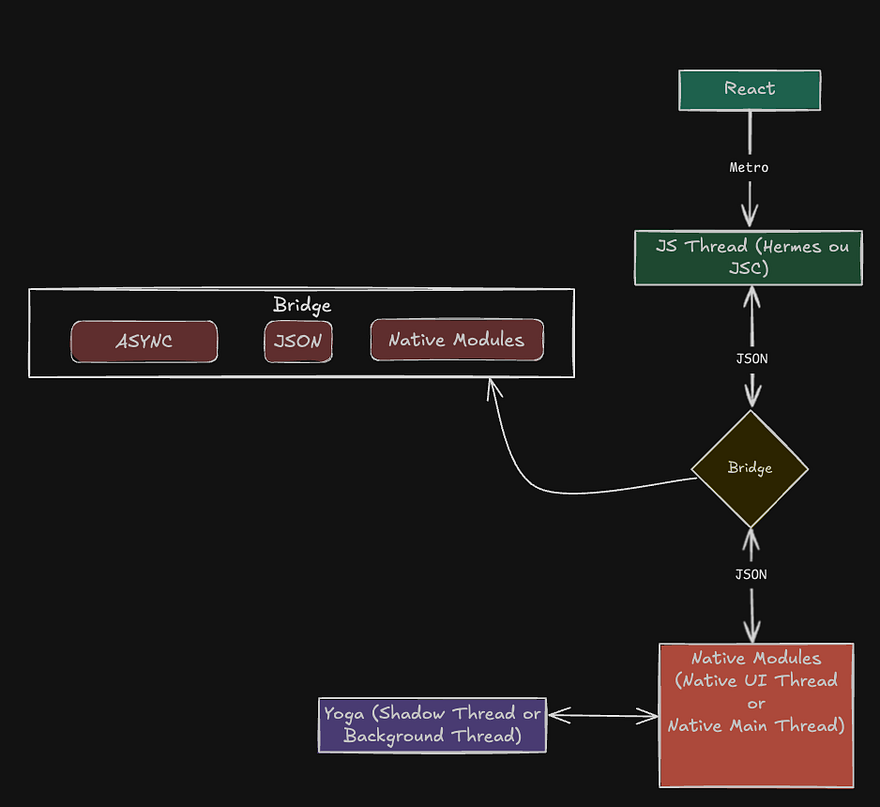

In summary, this is the architecture:

- JavaScript Thread: executes JS code, including logic, rendering, and interactions.

- Bridge (asynchronous): performs communication between JS code and native code using JSON.

- Main/UI Thread (Native): responsible for updating the user interface and handling touch events and animations.

- Shadow Thread (Yoga): performs layout calculations using the Shadow Tree, a virtual representation of the UI. The Yoga library, written in C++, is used to calculate Flexbox-based layout.

New React Native Architecture: Meet Fabric

In recent years, the React Native team has been working intensively to solve a long-standing pain point on the platform: performance in complex scenarios. This is how Fabric emerged, the new architecture that promises more fluidity, fewer bottlenecks, and more efficient communication between JavaScript and native modules.

Why change?

The previous React Native architecture was based on a bridge called Bridge (as explained earlier), which made communication between JavaScript code and the native side of the system (Android/iOS).

This model worked well - and still works - in most cases. However, in specific situations, it presented serious performance bottlenecks.

The cause? The Bridge was asynchronous and needed to serialize and deserialize JSON objects to transfer data between JS and native. This became a problem in scenarios like:

- Large lists (e.g., FlatLists with many items)

- Heavy animations

- Frequent interface updates

In these cases, the app could "stutter" - and this has an affectionate name within the RN team: "jank".

In the traditional architecture, React Native operated with three main threads:

- JavaScript Thread: executes the application logic.

- UI Thread: responsible for rendering visual elements.

- Module Thread: used for communication with native modules.

The problem is that, since the bridge needed to transfer data between these layers asynchronously and serialized, the UI Thread ended up waiting too long and showed noticeable slowness to the user.

The visual effect? That feeling that the interface tries to render and... freezes for an instant: "ja-ja-ja... rendered".

What is Fabric?

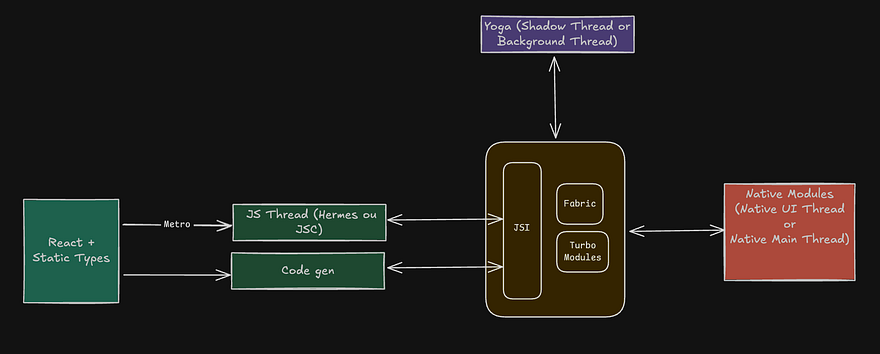

Fabric is the new architecture that replaces the use of the Bridge with a new model based on JSI (JavaScript Interface).

- Goodbye Bridge: there's no longer a need to send JSONs back and forth.

- Hello JSI: a C++ interface that allows JavaScript to directly access native modules - synchronously.

- More direct communication: this eliminates "jank" and improves performance in heavy UIs.

The new architecture is based on three central technologies:

JSI (JavaScript Interface)

A C++ layer that allows direct calls between JavaScript and native code, eliminating Bridge dependency.

Codegen

Automatically generates native code (Java, Objective-C, C++) and JavaScript code based on interfaces declared in TypeScript/Flow files.

TurboModules

Replace the old NativeModules. Now written in C++ and accessible via JSI, they are loaded on demand (lazy loading) and have much better performance.

Fabric

A new rendering system, also in C++, that replaces the previous layout tree. It works more efficiently with React reconciliation, providing UI rendered with lower latency.

A 6-year journey

Fabric development started in 2018. During this time, it was tested, validated, and refined. It first arrived as optional in React Native version 0.68.

Only in 2024 did it become enabled by default when creating a new project.

Does every app need this?

No. The truth is that the old architecture (with Bridge) still works perfectly in 99% of cases.

Fabric is more useful in specific scenarios, such as:

- Apps with rich interfaces and complex animations

- Intensive use of FlatLists

- Handling large volumes of data in the interface

If your app is simple, you probably won't even notice a difference. But for more robust apps, Fabric can represent a significant improvement in performance and fluidity.

Visual comparison of architectures

To make it easier to understand, see below the animations showing the communication flow in each architecture:

Old architecture (Bridge)

New architecture (JSI/Fabric)

Final considerations

Fabric is an important step in the evolution of React Native. It brings a more modern architecture, based on C++, and solves historical problems related to rendering and communication with native.

With it, React Native gets even closer to delivering truly native performance - without giving up the productivity of the JavaScript ecosystem.

Now that it's enabled by default, it's worth understanding how it works and exploring its benefits, especially if you're starting a new project or dealing with more demanding interfaces.